RLC Circuits (Alternating Current)

An RLC circuit contains different configurations of resistance, inductors, and capacitors in a circuit that is connected to an external AC current source.

Contents

Some Assumptions

Here are some assumptions:

- An external AC voltage source will be driven by the function \(V ={ V }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) } \), where \(V\) is the instantaneous potential difference in the circuit, \({ V }_{ o }\) is the maximum value in the oscillating potential difference, \(\sin { (\omega t) } \) is the graph that governs the oscillating nature, and \(\omega\) is the angular frequency.

- The capacitance of the capacitors is taken to be \(C,\) potential drop across it \({ V }_{ C },\) the inductance of the inductor \(L,\) potential drop across it \({ V }_{ L },\) the resistance of the resistor \(R,\) and the potential drop across it \({ V }_{ R }.\)

- Assume all the components in the circuit to be resistance-free except the resistor, of course.

Before dealing with RLC circuits, it is important to understand the effect of attaching R, L, and C components separately.

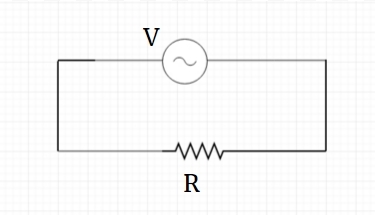

Resistor in an AC circuit

In a purely resistive circuit, we use the properties of a resistor to show characteristic relations for the circuit. Consider a time-dependent current \(I\) flowing through the circuit. Applying Kirchoff's voltage law for closed loops in the shown circuit, we get \(V= { V }_{ R } \).

Also, we know that according to Ohm's law, potential drop across a resistor is given by \({ V }_{ R } = IR\).

So, using the given piece of information, we can state that

\[\begin{align} V&=IR\\ { V }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) } &=IR\\ I&=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ R } \sin { (\omega t) } \\ I&={ I }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) }, \end{align} \]

where \({ I }_{ o }=\frac{{ V }_{ o }}{R}\) is the maximum value of current in the circuit.

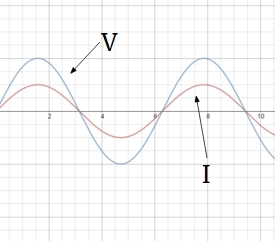

From the last derived function, we can clearly see that current in a purely resistive circuit is in phase with the applied voltage, i.e. whenever the voltage attains its maxima, so does the current, and whenever voltage attains its minima, so does the current.

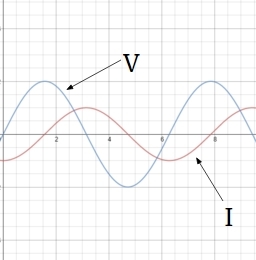

The following graph shows the variation of \(V\) and \(I\) with \(t\) for some \(\omega\). We take \(R >1\) as is clear from the graph.

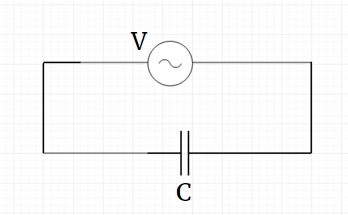

Capacitor in an AC circuit

In a purely capacitive circuit, we use the properties of a capacitor to show characteristic relations for the circuit. If we consider a time-dependent current \(I\) flowing through the following circuit, then by using Kirchoff's law of voltages for closed loops, we get \(V = { V }_{ C } \).

Now, from the theory of capacitors, we know that the potential drop across a capacitor of capacitance \(C\) is given by \({ V }_{ C } = \frac {Q}{C} \), where \(Q\) is the charge on the capacitor at any instant. So, using the given information,

\[\begin{align} V&={ V }_{ C }\\ { V }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) } &=\dfrac { Q }{ C } \\ Q&={ V }_{ o }C\sin { (\omega t) }. \end{align}\]

But current through the circuit is given by the rate of charge flow. So,

\[\begin{align} I&=\dfrac { d }{ dt } (Q)\\ &={ V }_{ o }C\dfrac { d }{ dt } \sin { (\omega t) } \\ &=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ 1/C\omega } \cos { (\omega t) } \\ &={ I }_{ o }\sin { \left(\omega t+\dfrac { \pi }{ 2 } \right) }. \end{align} \]

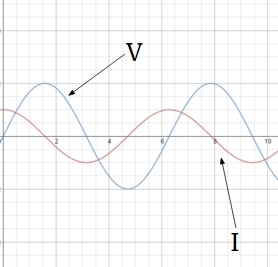

From, the final expression, it is clear that current in a purely capacitive circuit leads the applied voltage by a phase difference of \( \frac {\pi}{2} \), i.e. when voltage attains its maxima, current attains its minima, but being ahead of voltage.

Here, \({ I }_{ o }\) is the peak current during a complete cycle. This current is given by \(\frac { { V }_{ o } }{ 1/C\omega } \). Now, look at the term in the denominator. It acts as resistance in this circuit and is denoted by \({ X }_{ C }\) and is known as capacitive reactance. So, \({ X }_{ C }=\frac { 1 }{ C\omega }. \)

The following shows the graph of \(V\) and \(I\) with \(t\) for some \(\omega\). We consider \({ X }_{ C } > 1\) as is clear from the graph. Look how current always leads the voltage.

The following proof is to calculate the average power developed in a purely capacitive circuit over one time period.

We know that total power in any circuit is given by \(VI\). For the case of a capacitor, this can be written as

\[\begin{align} VI &=\big[{ V }_{ o } \sin{(\omega t)}\big] \big[{ I }_{ o } \cos{(\omega t)}\big]\\ P &= { V }_{ o } { I }_{ o } \sin{(\omega t)} \cos{(\omega t)}\\ &= \dfrac {{ V }_{ o } { I }_{ o }}{2} \sin{(2\omega t)}. \end{align}\]

Let's try to calculate the total power developed in the circuit for an entire cycle, i.e. \(t=0\) to \(t=\frac {2\pi}{\omega} \). So,

\[\bar { P } =\dfrac { { V }_{ o }{ I }_{ o } }{ 2 } <\sin { (2\omega t)> }. \]

But we know that the average of sine function over an entire cycle is zero. Therefore

\[\\ \bar { P } = 0.\]

It must be remembered that although capacitive circuits do dissipate power in an instant, the average power is what's zero for the circuit.

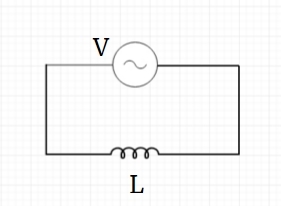

Inductor in an AC circuit

In a purely inductive circuit, we use the properties of an inductor to show characteristic relations for the circuit. Considering the flow of a time-dependent current \(I\) through the circuit shown below enables us to use the concept of induced emf due to the changing current in the inductor. So, according to Kirchoff's voltage law for closed loops, we get \(V={ V }_{ L }.\)

Also, from the theory of electromagnetism, we say that potential across the inductor is given by

\[{ V }_{ L } = L\dfrac {d}{dt} I.\]

So, using the piece of information we have, we get

\[\begin{align} V &=L\frac{d}{dt}(I) \\ \\ V_o \sin(\omega t) &=L \frac{d}{dt}(I) \\ \\ dI&=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ L } \sin { (\omega t) }\, dt\\ \\ \displaystyle\int { dI } &=\displaystyle\int { \dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ L } \sin { (\omega t) }\, dt } \\ \\ I&=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ L\omega } \big(-\cos { (\omega t)\big) } +K\\ \\ &=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ L\omega } \sin { \left(\omega t-\dfrac { \pi }{ 2 } \right) } +K. \end{align}\]

However, since the voltage oscillates between a maximum and a minimum value following a sine graph, it is logical to assume the same for the current. Hence, we get the integration constant \(K= 0\).

So, \(I={ I }_{ o }\sin { \big(\omega t-\frac { \pi }{ 2 } \big) } \), where \({ I }_{ o } \) is the peak current in the circuit and is given by \({ I }_{ o }=\frac { { V }_{ o } }{ L\omega }.\) Looking at the term in the denominator, we infer that it acts as the resistance for this circuit and is known as Inductive reactance, \({ X }_{ L } \). So, \( { X }_{ L } = L\omega\).

Finally, we can also deduce from the formula of time-dependent current that it lags the applied potential difference by a phase of \(\frac {\pi}{2}\), which can be clearly seen from the graph shown below.

The proof for power developed in a purely inductive circuit is extremely identical to the power developed in the case of a purely capacitive circuit. This is because, in both these cases, the phase difference between voltage and current is the same, i.e. \( \frac {\pi}{2}, \) which results in the average power of the circuit to come out to be 0.

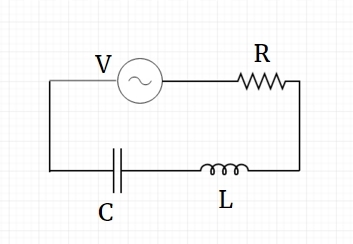

RLC Circuit (Series)

So, after learning about the effects of attaching various components individually, we will consider the basic set-up of an RLC circuit consisting of a resistor, an inductor, and a capacitor combined in series to an external current supply which is alternating in nature, as shown in the diagram.

The components are in series, so as a result the current passing through them will be the same. Let this current be \(I\) which varies with time. Now, using the values of potential drop across every component, and using Kirchhoff's voltage law for closed loops, we can clearly make out that:

\[\begin{align} V &=IR+L\frac{dI}{dt} +\frac{Q}{C} \\ V_o \sin(\omega t) &=\frac{Q}{C} + R\frac { dQ }{ dt } +L\frac { { d }^{ 2 }Q }{ d{ t }^{ 2 } }. \end{align}\]

This is a differential equation in \(Q\) which can be solved using standard methods, but phasor diagrams can be more illuminating than a solution to the differential equation.

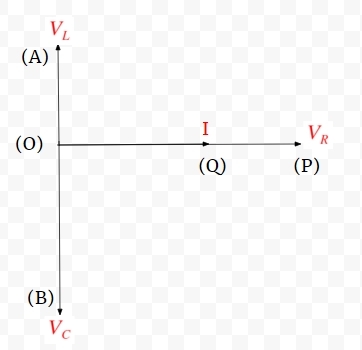

Although currents and voltages are scalar in nature, yet sometimes they are assumed to have a direction which is related to their phase differences with respect to each other. Phasor diagrams are such diagrams that represent these scalar quantities with a direction and help us compute our results better.

DERIVATION USING PHASOR DIAGRAMS

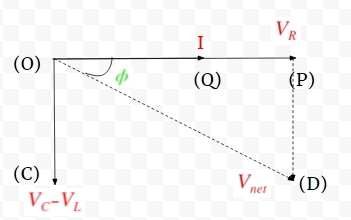

Since the current through all the components is same, we construct a ray \(OQ\) that shows the direction of the current, which will be the same for all the components. Now, from the derivations of purely resistive, inductive, and capacitive circuits, we have seen that voltage and current have a particular phase difference between each other for every component. So, considering these facts in mind, we complete the diagram by producing a ray \(OP\) parallel to \(OQ\) that represents the voltage across the resistor. Similarly, we construct a ray \(OA\) at an angle of \(+ \frac {\pi}{2} \) with respect to current. This represents the voltage across the inductor. Finally, construct a ray \(OB\) at an angle of \(- \frac {\pi}{2} \) with respect to \(OQ\). This shows the voltage across the capacitor. We get something like this:

Looking at the diagram, we see three vectors \(OA, OB,\) and \(OQ\) which represent voltages across single components. Using basic vector algebra, and considering potential drop across the capacitor to be more than that for the inductor, we see that the net voltage is along the diagonal of the so formed parallelogram \(COPD\), and is given by the vector \(OD\). Also, let the angle between \(OD\) and \(OQ\) be given by \(\phi\). As you can see, \(\phi\) here represents the overall phase difference between voltage and current.

So, we infer that

\[\begin{align} {V_\text{net}}^2 &={ { V }_{ R } }^{ 2 }+{ ({ V }_{ C }-{ V }_{ L }) }^{ 2 }\\ &={ (IR) }^{ 2 }+{ { (I }{ { X }_{ C } }-I{ X }_{ L }) }^{ 2 }\\ &={ I }^{ 2 }\left[ { R }^{ 2 }+{ ({ X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L }) }^{ 2 }\right] \\ \\ \frac { { V }_\text{ net } }{ I } &=\sqrt { { R }^{ 2 }+{ ({ X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L }) }^{ 2 } } \\ &=Z. \end{align}\]

Here, \(Z\) is known as the impedance of the circuit and plays the role of net resistance. Alternatively, \(Z\) can also be written as

\[Z=\sqrt { { R }^{ 2 }+{ \left(\frac { 1 }{ C\omega } -L\omega \right) }^{ 2 } }. \]

Also, from the diagram, we can see that the phase difference \(\phi\) is related to voltage as

\[\begin{align} \tan { \phi } &=\frac { { V }_{ C }-{ V }_{ L } }{ V_{ R } }\\ &=\frac { { X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L } }{ R } \\ \phi &=\arctan { \frac { { X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L } }{ R } }. \end{align}\]

So, all in all, in a series RLC circuit, if the applied voltage is given by \(V = { V }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) } \), then the current through the circuit is represented by \(I={ I }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t+\phi ) },\) where

\[{ I }_{ o }=\dfrac { { V }_{ o } }{ \sqrt { { R }^{ 2 }+{ ({ X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L }) }^{ 2 } } }\quad\text{and}\quad \phi =\arctan { \dfrac { { X }_{ C }-{ X }_{ L } }{ R } }. \]

The following is the proof for the power developed in a series LCR circuit:

The power developed in the circuit at time \(t\) is

\[\begin{align} P &=VI\\ \\ &=\big[{ V }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t) } \big] \big[{ I }_{ o }\sin { (\omega t+\phi )\big] } \\ \\ &=\frac { { V }_{ o }{ I }_{ o } }{ 2 } 2\sin { (\omega t) } \sin { (\omega t+\phi ) } \\ \\ &=\frac { { V }_{ o } }{ \sqrt { 2 } } \frac { { I }_{ o } }{ \sqrt { 2 } } \big[ \cos { \phi } -\cos { (2\omega t+\phi )\big] }. \end{align}\]

Now, putting in \(\frac { { V }_{ o } }{ \sqrt { 2 } } = { V }_\text{rms}\) and \(\frac { { I }_{ o } }{ \sqrt { 2 } } = { I }_\text{rms},\) we end up with

\[P={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}\big[ \cos { \phi } -\cos { (2\omega t+\phi ) } \big]. \]

Hence, the average power \(\bar { P } \) is given by

\[\bar { P } ={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}\big[ <\cos { \phi } >-<\cos { (2\omega t+\phi ) } >\big]. \]

Now, since \(\cos{\phi}\) is independent of time, its average is \(\cos{\phi}\) only. Also, the average of \(\cos { (2\omega t+\phi ) } \) across one cycle is 0. So, we get the final formula for average power to be

\[\bar { P } ={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}\cos { \phi } ={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}\frac { R }{ Z }. \]

So, it can be seen that unlike a simple DC circuit, the power developed in an LCR circuit is also dependent on the value of \(\cos {\phi}\) which is defined as the power factor of the circuit.

Resonance

Resonance in case of an LCR circuit refers to the condition when the potential drop across the inductor is the same as the potential drop across the conductor, or \({ V }_{ L } = { V }_{ C}.\)

The basic condition for resonance can be easily derived. Since \({ V }_{ L } = { V }_{ C},\) we can write

\[\begin{align} I{ X }_{ L }&=I{ X }_{ C }\\ L{ \omega }_{ r }&=\frac { 1 }{ C{ \omega }_{ r } } \\ { \omega }_{ r }&=\frac { 1 }{ \sqrt { LC } }. \end{align} \]

Here \({ \omega }_{ r }\) represents the resonant frequency of the circuit, or the frequency of the applied voltage that causes a condition of resonance. Since \({ X }_{ L }={ X }_{ C },\) from the formula for impedance of the circuit, we can easily derive the relation that \(Z=R;\) in other words, the impedance of a circuit in case of resonance is minimum, or conversely, the current in the circuit is maximum.

This property of resonant circuits is used amazingly in television and radio sets. Quite basically, such a device can be viewed to consist of an LCR circuit in it. When it receives an electromagnetic signal of some frequency, this signal is converted into an electrical signal which tends to be the AC source for the circuit. Now, for every channel, there's a particular configuration of inductor and capacitor used. So, if the received frequency matches with resonant frequency for that particular channel, then the current in that circuit goes to maximum and the signal is said to be accepted.

On the other hand, if it does not match the resonant frequency, then the current stays less than the maximum current and the signal is said to be rejected or denied.

Power in a resonating LCR circuit

We know that average power of any LCR circuit can be given by \(\bar { P } ={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}\cos { \phi }. \)

But for a circuit in which the inductive and capacitive reactance are equal, it can be easily inferred that \(\phi=0\), or \(\cos { \phi }=1\). Plugging this value in the formula, we get

\[\bar { { P }_{ r } } ={ V }_\text{rms}{ I }_\text{rms}.\]

Moreover, since \(Z\) attains its minima, the current in the circuit or \({ I }_\text{rms}\) attains its maxima. Hence, power developed in case of a resonating circuit is maximum.

You are ready for your next vacation to a land of peacefulness. The only thing between you and your destination is a shameless metal detector that requires you to walk through it without making it go beep!

You took all the articles off but forgot your watch, and as soon as you walked in, the alarms went off and you are required to walk through again, removing your watch this time. You're good to go and you enter your airplane where you sit down and work out the incident at the airport.

You do know that the metal detector is just a simple application of an LCR circuit. The next piece of info you know is that the sound alarm that blared off was most likely a basic one which requires an RMS current of \(10\text{ A}\) to go off.

Consider the LCR circuit to be made up of a sound source of resistance \(5\, \Omega,\) an ideal inductor of \(2\text{ mH},\) and an ideal capacitor of \(20\text{ pF}.\)

All you need to do is to work out the angular frequency of the current that your watch generated, i.e. \(\omega\) and the RMS value of the alternating voltage for the circuit, i.e. \({V}_\text{rms}.\)

Submit your answer as \(\frac {\omega} {{10}^{7}} + {V}_\text{rms}.\)