Chess Puzzles - Opening Strategies

In chess, an opening is a general set of moves one memorizes for play in the early stage of the game. Once the position is no longer known to either player, the opening is over and the game transitions into the middlegame.

Depending on skill level and style of play, various different opening strategies are possible; in fact, dozens of openings routinely see play at the highest level of chess. Innovation within opening lines happens quite routinely, and it is not rare for a novelty (a previously unseen move) to be played dozens of moves into the game, so the study of openings is important to gain an edge as early as possible.

Contents

Opening Principles

Almost all openings share three major goals, with the exception of a few lines that have concrete reason to ignore principles; these lines, however, are very rare and eventually have the same general goals as more typical openings. These main goals are as

- development, which roughly means moving pieces from their starting squares to squares where they more directly affect the board,

- center control, which refers to control of the four squares e4, d4, e5, and d5 (the ones at the center of the board), and

- king safety, which almost exclusively means castling as soon as possible.

Of course, players also attempt to disrupt their opponent's execution of the above goals; for example, a typical strategy involves accepting a strategic weakness (such as doubled pawns) in order to prevent the opponent from castling.

While practically all openings share these general goals, different classes of openings weigh them differently. An aggressive-minded player might ignore their own king safety in favor of rapid development, as a lead in development offers more attacking chances. More conservative players may favor central control over fast development, aiming for a solid position with few weaknesses. Those looking for long-term structural weaknesses might temporarily concede the center in order to gain a different, more permanent advantage, such as the bishop pair or the doubling of the opponent's pawns. Even within these broad categories, there is much room for experimentation, and the lines between them often blur throughout the course of a game.

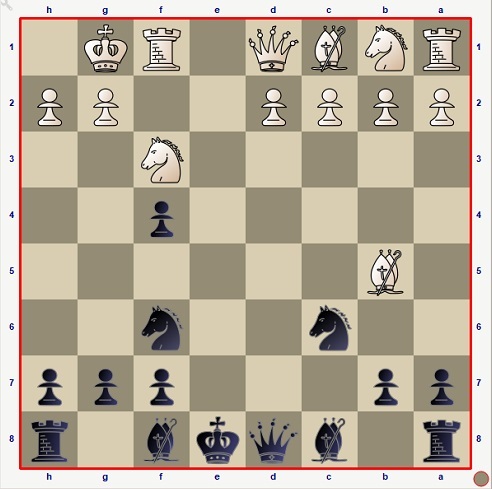

In the following position, which of the four given moves is strongest for White?

If it is white's turn to move, which of the following is the best retreat move for the white bishop at b5?

If it is white's turn to move, which of the following is the best retreat move for the white bishop at b5?

Black to move. What is the best move for black?

Black to move. What is the best move for black?

Classical Openings

The classical openings, so named for their adherence to classical principles, weigh the three major goals roughly equally with a slight emphasis on central control. In general, these openings lead to solid, safe positions, and are thus the weapon of choice for strategic, long-term players.

Classical openings are also often employed by players facing stronger opposition, as their safe nature makes draws more likely. However, it is unclear whether this widely-used strategy is in fact optimal, as stronger players often use the low-risk nature of the position to gradually outplay their opponent. Regardless, it is generally the case that the classical openings are more forgiving towards mistakes, as their effect is generally limited to a somewhat minor strategic consideration (rather than the loss of something more permanent, such as material).

An excellent example is the Italian game, characterized by the moves

- e4 e5

- Nf3 Nc6

- Bc4 Bc5

- c3 Nf6

- d3 O-O

- O-O.

Both sides have successfully completed their main goals, having castled, contended key squares in the center, and developed several pieces. The game is roughly equal, which is unsurprising considering the relatively symmetric nature of the position.

Hypermodern Openings

The hypermodern openings, named for their clash with the classical openings, are characterized by controlling the center with pieces, rather than by occupying it with pawns. They often include the use of the fianchetto, or moving a b/g-pawn in order to place the bishop on the long diagonal, and they also concede a large amount of space (roughly speaking, controlled squares) to the opponent.

In particular, there is a heavy emphasis on development, with king safety and central control taking a temporary backseat. The main goal is to demonstrate that the center occupied with pawns is naturally unstable, and that it can be successfully challenged by the opponent's better-placed pieces.

Hypermodern openings are often employed by players who prefer a more dynamic struggle, as the resulting positions tend to be highly unbalanced. For this reason, they are also often used by stronger players looking to avoid draws against lower-rated opposition, as they are more likely to handle the resulting imbalances better. Additionally, the hypermodern openings are generally considered to be faster-paced and more exciting than the classical ones, so they are especially popular outside of top-level chess.

A good example of a hypermodern opening is the Pirc defense, characterized by the moves

- e4 d6

- d4 Nf6

- Nc3 g6.

Black has chosen to allow White a strong center, choosing instead to fianchetto the bishop to g7 and quickly castle. Later on, Black will attack White's center with moves such as ...c5 and ...e5. If the center is successfully disrupted, Black will have a good game due to the strength of the bishop on the long diagonal, while White has some trouble finding natural squares to develop his pieces to while simultaneously fortifying the center. Nonetheless, White stands good chances of keeping his center intact, which would provide the basis for other plans such as an attack or space-gaining operations. Overall, the Pirc is considered objectively slightly dubious but practically very playable, especially for non-titled players.

Gambits

Gambits are characterized by the sacrifice of material to rapidly develop pieces. Usually, this means intentionally giving up a pawn that can be recaptured by a favorable developing move, or by ignoring the threat to a pawn and developing pieces anyway. Depending on the particular line, the goal may be to recover the pawn quickly (while maintaining the development lead), or to exploit the development lead through use of an attack or another permanent positional trump. In general, these openings lead to extremely fast-paced games where tactical ability is paramount, and therefore aggressive, dynamic, and young players often employ gambits.

Gambits can be further divided into two broad categories: true gambits, in which regaining the material is not the main goal (in the sense that the opponent can feasibly choose to keep the material, if they so wish), and pseudo-gambits, in which it is unwise for the opponent to accept the gambit. For example, the queen's gambit (1. d4 d5 2. c4) is effectively a pseudo-gambit, as accepting the offered pawn is known to lead to a relatively bad position. In contrast, the Smith-Morra gambit (1. e4 c5 2. d4 cxd4 3. c3) is a true gambit, as White will not regain the material unless Black chooses to offer it back.

An example of a gambit is the King's gambit, characterized by the moves

- e4 e5

- f4.

If the gambit is accepted, White will compensate for the pawn by forming a strong uncontested center (with a later d4), and using the semi-open f-file for operations with his rook after castling. Black can choose to retain the pawn, for example after 2... exf4 3. Nf3 g5!?, which is very dangerous for both sides, or to decline the gambit with a move like 2... d6. Black can even choose to play a gambit of his pawn, with the line 2... d5!? 3. exd5 e4. This line was quite popular in early competitive chess, but has largely fallen out of favor in modern chess due to the advent of computer chess.

Other Categories

While the above categories describe most chess openings, there remains plenty of room for other openings that do not fit neatly into this classification scheme. For instance, the Sicilian defense (1. e4 c5)--one of the most popular openings in modern chess--allows the opponent rapid development in exchange for the stronger center, and openings such as the English (1. c4) only loosely correlate to hypermodernism. Though these openings do not have broad categories to assign them to, their division into general principles remains quite evident, and therefore understanding the relative value of the main goals is key to understanding the opening phase of the game. Of course, very little is known about their objective relative values, so (at least for now) the choice of opening is almost exclusively a personal decision.

Tips on Opening

- Don't memorize the opening lines. Just be familiar with the e4 and d4 openings because the other openings came from these openings. Being familiar means to understand every move.

- Do not be creative especially if you are not prepared. Focus on simple moves (moves that do not need calculation; in short, moves that you are familiar with).

- Avoid tactical openings. These are the openings with traps (sometimes with the help of an engine). Most beginners memorize these traps.