Chess Puzzles - Rook Strategies

In Chess, the rooks are pieces that can move any number of squares in each of the four cardinal directions (informally: up, down, left , and right), so long as they are not blocked by another piece.

Left: the movement of a rook on an empty board. The rook can move to any square a red arrow passes through.

Right: the movement of a rook on an occupied board. The rook can move to any square a red arrow passes through, including capturing the black pawn

Left: the movement of a rook on an empty board. The rook can move to any square a red arrow passes through.

Right: the movement of a rook on an occupied board. The rook can move to any square a red arrow passes through, including capturing the black pawn

The rook is the second strongest piece behind the Queen, with a Material score of 5 (compared to the Queen's 9). In algebraic notation, the rook is abbreviated by the letter 'R'. The rook is also one of the four pieces that a player can promote to, though this is rarely seen as its main purpose is to avoid Stalemate.

Contents

General strategy

At the beginning of the game, and through the opening phase, the rooks are generally blocked by friendly pieces and do not substantially contribute to the game (indeed, at the beginning of the game, the rooks have no legal moves at all). This leads to a major opening goals for the rooks:

To move the rooks onto open (or as open as possible) files.

The rooks are also at their strongest when they are connected, because they are able to support one another and thus fully control a file (or rank). Thus another major goal is

To connect the two rooks, most often by moving pieces off of the back row.

Finally, Rooks indirectly participate in castling, which both achieves the purpose of improving king safety and working towards the two goals above.

Rook Synergy

The two rooks work best together due to their ability to support each other, which means they can take full control of a single file (or rank) without being captured, and they can also control adjacent files. This makes them very useful for checkmating the enemy king, since the king can be slowly forced to the edge of the board where it only has access to 2 files (which can both be controlled by the rooks).

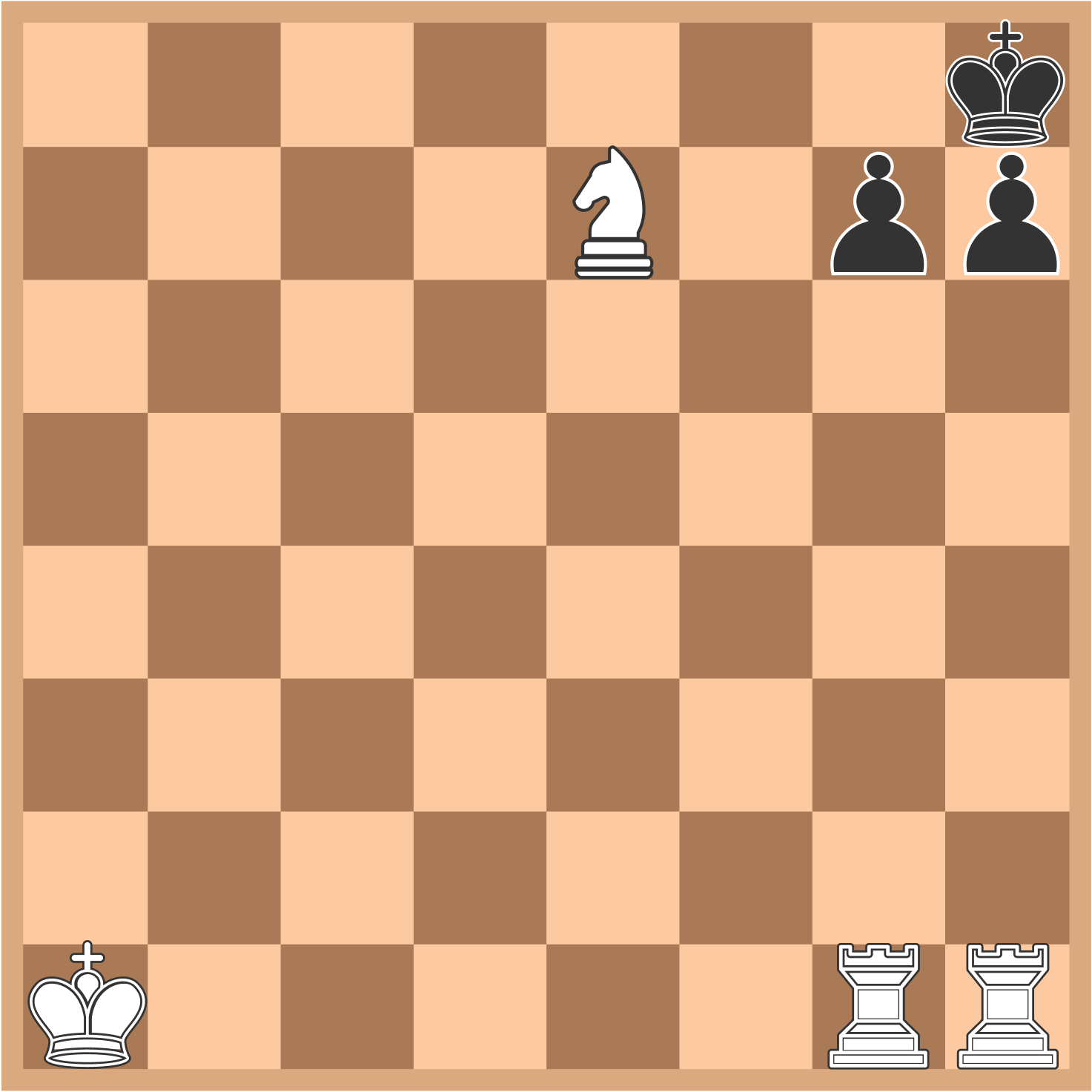

In the position above, the black king is already pinned in a corner, meaning that it only has access to the g- and h-file. If White can control both of these files at the same time, the black King would be checkmated, so White can win quickly by first taking control of the g-file (which forces the black King to stay on the h-file), then the h-file:

- Rg2 (or Rg1) Kh7

- Rh1# (or Rh2#, if 1. Rg1 was played)

It is also possible to achieve this along the ranks, since the black king only has access to the 7th and 8th ranks:

- Rb7 (or Ra7) Kg8

- Ra8# (or Rb8#, if 1. Ra7 was played)

Rooks that are "doubled", or placed on the same file or rank, are strong because they can safely travel along that file/rank, with the support of the other. This is especially useful for giving checks, since the enemy king will not be able to capture the checking rook (as it is defended by the other):

In the above position, White can give checkmate by giving checks along the 7th rank:

- Rh7+ Kg8

- Rag7#

A final typical way in which the two rooks synergize is a situation in which one rook sacrifices itself to open a file (usually the h-file), so that the other rook can take full control of it.

In the above position, White can give checkmate by clearing the h-file:

- Rxh7+ Kxh7

- Rh1#

Castling

Castling is a special move in which the king and rook move simultaneously towards each other, so long as three conditions are met:

- Both the king and the rook are on their original squares, and both lie on the same rank (the second part of this condition eliminates the possibility of castling with a promoted rook)

- The king is not in check, the target square of the king (2 squares towards the rook) is not under attack, and the square between the king and the target square (1 square towards the rook) is not under attack

- There are no pieces (of either color) between the king and rook

If all these conditions are met, the king is allowed to move two squares towards the rook, with the rook moving "over" it by one square.

Left: the position before castling kingside. Right: the position after castling kingside

Left: the position before castling kingside. Right: the position after castling kingside

Castling is important to achieve early, because it helps achieve three purposes:

- The king is made safer by getting away from the center of the board

- The rook is closer to the center, and thus (most likely) to open files

- The two rooks are closer to becoming connected, since multiple pieces between them have already been moved

In fact, castling occurs literally as early as possible (move 4) in a variety of popular openings, such as some lines in the Nimzo-Indian defense. As a result, castling is rarely seen in practical exercises as it has almost always been performed by the time a position becomes interesting (and castling, due to the first condition, can only be done once per game). When seen later on, it is usually used to perform a double attack with both the king and the rook, usually with the rook giving check.

In the above position, White wins material with

- O-O-O+!

Both giving check and attacking the rook simultaneously.

Additionally, many compositions make use of castling as an aesthetic tool, as they are not constrained by the practical considerations of castling early. In fact, whenever castling might be legal (i.e. the three conditions above are satisfied) in a problem, it is assumed to be legal (meaning that it is assumed the king and rook have not previously moved) unless it can be conclusively proven otherwise.

In the above position, White has a mate in 2 available with

- Qa1! Kd8 (or 1... Kf8 2. Qxh8#, or 1... any pawn move 2. Qa8#)

- Qa8#

The key point is that Black cannot play 1... O-O, since his last move must have been with the king or the rook (since it cannot have been with any of the pawns, given that they are all on their starting squares), and so castling is illegal.

Endgames

Rooks are most important in the Endgame, as they are statistically the most likely to survive until that phase. In fact, almost 90% of endgames are so-called "rook endgames", meaning that only rooks and pawns remain.

The most important rook endgames are those in which one side has a rook and a pawn, and the other side has only a rook, because many endgames could potentially lead to them as a conclusion. In particular, it is important to know when the side with the extra pawn can win, and when the side with only the rook can successfully draw.

As a general rule of thumb, if the defending side can maneuver his king to be in front of the opposing pawn, the position is likely drawn. Conversely, if this is not possible, the position is usually won. This principle is most evident in the difference between the two most famous (and important) endings: the Lucena position and the Philidor position.

The Lucena position is a position in which the stronger side can win, using a technique known as "bridge building".

White has managed to prevent the Black king from getting in front of the pawn, by blocking with his own king, but now must find a way to get his own king out of the way. The most naive way of doing this is insufficient:

- Rc2+ Kb7

- Kd7?! Rd1+

- Ke6 Re1+

- Kd6 Rd1+

- Kc5 Re1

and so on, where White cannot make progress due to the constant checks. To avoid them, White needs a way to shelter his king without leaving the d/e-files (as then the pawn gets attacked and the king must move back), for which he needs the assistance of the rook:

- Rc2+ Kb7

- Rc4! Re2

- Kd7 Rd2+

- Ke6 Re2+

- Kd6 Rd2+

- Ke5 Re2+

- Re4

and Black cannot give any more checks.

The Philidor position is a position in which the weaker side can draw, by keeping the opposing king far enough back:

White draws easily with

- Rh3!

Black will never be able to move the king forward without first advancing the pawn, since checks make no progress (White simply moves the king back and forth). However, if Black moves the pawn forward, White simply returns with the rook, and then gives checks ad infinitum:

- Rh3 e3

- Rh8 Kd3

- Rd8+ Ke4

- Re8+ etc.

thus holding the draw as Black cannot make progress.

It is also possible to defend in a slightly different manner, by keeping the Black king tied to the defense of the pawn:

- Re8!? Ke3

- Kf1 Ra1+

- Kg2

and Black again cannot make progress, since the king is unable to advance without giving up the pawn.

Though these two positions are the most important for the study of rook endgames, equally important are the two general principles they demonstrate:

- The rook should be behind passed pawns, since this allows the pawn to advance freely

- The king should be cut off by the rook as much as possible, to keep it out of the game (e.g. to keep it from getting in front of the pawn)

In fact, these considerations are so important that it is often worth considering sacrificing a pawn to achieve them.