Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis is a theory that market prices fully reflect all available information, i.e. that market assets, like stocks, are worth what their price is. The theory suggests that it's impossible for any individual investor to leverage superior intelligence or information to outperform the market, since markets should react to information and adjust themselves. Any intelligent investor buying a stock is doing so because they believe the stock is worth more than the data (typically historical returns, projected returns, macroeconomic trends, industry trends, etc.) support it being worth. They think that the data is wrong and undervaluing the stock. Economists counter that investors are either buying riskier stocks and undervaluing the risk or succeeding through chance. Put another way, as Burton Malkiel says in his book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street, the efficient market hypothesis means that "a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the Wall Street Journal could select a portfolio that would do as well as the experts."

As this, essentially, suggests that the tens of thousands of experts who work as active investors are worthless, it has been heavily critiqued. These critiques, themselves, come from successful investors like Warren Buffett who points to the undervaluing of "value stocks" (as opposed to the sexier growth stocks), behavioral economists who point to humanity's inefficiencies, and experts who have used valuations techniques, like dividend yields and price-earnings ratios to generate higher returns.

French mathematician, Louis Bachelier is considered to many to be the first to apply probability theory to markets.[1] Though his work didn't reach a wide audience until the 1950s and 1960s. Eugene Fama is credited, over the course of his career, for much of modern theories of efficient markets, expanding Bachelier's initial work, and starting with Fama's publication, in 1965 of his PhD thesis. Both used mathematical models of random walks and were influenced by Hayek's 1945 argument that markets are the most efficient way to aggregate information.

Contents

- Weak, Semi-Strong, and Strong Efficiency

- Attacks (and responses to attacks) on the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Response to attacks on the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- How Stocks Respond to Interest Rates

- Investment Strategies for Proponents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Possible Paradoxes

- References

Weak, Semi-Strong, and Strong Efficiency

Efficient markets are said to exist in varying degrees of efficiency, generally categorized as weak, semi-strong, and strong. These degrees of strength pertain markets responding to information.

In strong efficiency markets, all public and private information is reflected in market prices. This includes insider information (and thus if there are laws prohibiting insider information from being made public, strong efficiency is not in place). In such a market investors, overall, cannot earn excess returns because the market has priced in historical and future (trend) information. Those individual investors are said to consistently outperform the market, maybe doing so simply because any log-normal distribution of thousands of fund managers will include some that consistently outperform the average.

In semi-strong efficiency markets, investors respond very quickly to new information. Because of the speed of information being responded to, investors cannot make excess returns from information. (There are cases where investors set up communications networks to arbitrage information faster than other investors could, but this is a market inefficiency that was corrected for over time). The contention around semi-strong markets is that they have factored in all available information, so fundamental and technical analysis (i.e. doing analysis from available information) does not reveal underpriced securities for investors to make excess returns from.

In weak efficiency markets, there is a chance that investors can make some money in the short term, that markets only reflect all currently available information in the long term. However, markets do, eventually, reflect all available information, and it contends that historical data does not have a relationship with future prices, i.e. Investors cannot use past data to predict future prices and gain excess returns.

There is one anomaly to weak efficiency, one that even Fama has acknowledged, and that has been observed in multiple international markets: the momentum effect. Stocks that have historically gone up in the past 3-12 months, tend to continue to go up. Stocks that have historically gone down in the past 3-12 months, tend to continue to go down.

Attacks (and responses to attacks) on the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economists (and behavioral psychologists) study the cognitive bias that humans have and that lead to irrational decision making. At a high level, these biases could prove that investors are inefficient, both signaling that they aren't going to beat the market (consistent with EMH) and that there are arbitrage opportunities to exploit their inefficiencies (inconsistent with EMH). For instance, people have been shown to employ something called hyperbolic discounting, i.e. given two rewards, humans tend to prefer the reward that comes sooner to the one that comes later. And investment fund managers can suffer from this same bias; in some cases their bonus this year is predicated on their returns this year, not their long-term returns, potentially leading to making okay short-term decisions at the expense of great long-term options. Other economists point to herd mentality, loss aversion, and the sunk cost fallacy for reasons why investors will not outperform the market.

Bubbles

Stock market bubbles--like the dot-com bubble of the late 90s, and the housing market bubble of the early 2000s--are acknowledged analomies in the EMH. For a period of time markets (and investors) systematically overestimated a set of assets, until they came crashing down. Economists contend that even rare statistical events are allowed under log-normal distributions. But investors counter that there is an arbitrage opportunity here--that some savvy investors made money by realizing these assets were inflated, and that once the market crashed, the assets were deflated. Economists, in turn, counter back that it's hard or abnormal to realize this in real time, and that few investors arbitraged successfully. For instance, in the case of the dot-com bubble, the available information actually supported some of the prevailing high valuations. With internet usage doubling every few months, one could conceive that this would continue (as it inevitably did with a handful of dot-com era companies--Amazon, Ebay, Yahoo--deservedly achieving the same or higher valuations that they had back in the late 90s).

Successful Investors and Value Investing

Some notable investors, Warren Buffett being one, contend that investment techniques, like value investing, have let them outperform the market, even when most other investors do only as well as index funds would. Value investing is a technique, pioneered by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, in which the investor, generally, buys securities that are underpriced according to some form of analysis (see dividend yields and P/E ratios below).

In a famous 1984 lecture at Columbia Business School, Warren Buffett talked about nine successful investors that are not merely statistically outliers on a log-normal distribution curve of efficient markets, “So these are nine records of 'coin-flippers' from Graham-and-Doddsville. I haven’t selected them with hindsight from among thousands. It’s not like I am reciting to you the names of a bunch of lottery winners...I selected these men years ago based upon their framework for investment decision-making...It’s very important to understand that this group has assumed far less risk than average; note their record in years when the general market was weak. While they differ greatly in style, these investors are, mentally, always buying the business, not buying the stock. A few of them sometimes buy whole businesses. Far more often they simply buy small pieces of businesses. Their attitude, whether buying all or a tiny piece of a business, is the same. Some of them hold portfolios with dozens of stocks; others concentrate on a handful. But all exploit the difference between the market price of a business and its intrinsic value.”

| Fund | Manager | Fund Period | Fund Return | Market return |

| WJS Limited Partners | Walter J. Schloss | 1956–1984 | 21.3% | 8.4% (S&P) |

| TBK Limited Partners | Tom Knapp | 1968–1983 | 20.0% | 7.0% (DJIA) |

| Buffett Partnership, Ltd. | Warren Buffett | 1957–1969 | 29.5% | 7.4% (DJIA) |

| Sequoia Fund, Inc. | William J. Ruane | 1970–1984 | 18.2% | 10.0% |

| Charles Munger, Ltd. | Charles Munger | 1962–1975 | 19.8% | 5.0% (DJIA) |

| Pacific Partners, Ltd. | Rick Guerin | 1965–1983 | 32.9% | 7.8% (S&P) |

| Perlmeter Investments, Ltd | Stan Perlmeter | 1965–1983 | 23.0% | 7.0% (DJIA) |

| Washington Post Master Trust | 3 different managers | 1978–1983 | 21.8% | 7.0% (DJIA) |

| FMC Corporation Pension Fund | 8 different managers | 1975–1983 | 17.1% | 12.6% (Becker Avg.) |

These, and other value investors, look at fundamental analysis like the following to determine predictable patters:

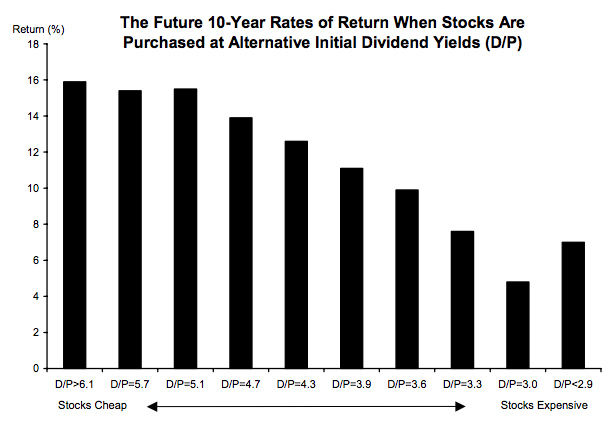

Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by dividend yields[2]

Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by dividend yields[2]

Have high dividend yields: Dividends are cash returns that companies choose to pass on to their shareholders. For instance a company might return $100 million to it's shareholders by giving $1 for each of the 1 million shares outstanding. The chart to the right takes the dividend yield of the S&P 500 each quarter from 1926 - 1990 and then finds the ten-year return (through 2000). It shows that investors have earned a greater rate of return from high-dividend yielding stocks. However, as Malkiel notes: "These findings are not necessarily inconsistent with efficiency. Dividend yields of stocks tend to be high when interest rates are high, and they tend to be low when interest rates are low (see below). Consequently, the ability of initial yields to predict returns may simply reflect the adjustment of the stock market to general economic conditions. Moreover, the use of dividend yields to predict future returns has been ineffective since the mid-1980s. Dividend yields have been at the three percent level or below continuously since the mid-1980s, indicating very low forecasted returns."[2] This low-dividend trend has continued through the 21st century, with many companies electing for share repurchases as a theoretically "better way" to return capital to investors.

Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by P/E ratios[2]

Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by P/E ratios[2] Have low price-to-earning multiples or have low price-to-book ratios (P/E ratios): Another favored metric of value investors is the Price to earnings ratio. Some companies, like Facebook, have relatively high multiples of earnings, as of December 1st 2016, it was \(\approx 44\) meaning that the total return Facebook earned for the previous four quarters was \(\frac{1}{44}\)th of the stock price. Or, put another way, it would take 44 years, at the current rate of net earnings for Facebook to pay an investor back for their purchase price. The key here being that investors who are choosing to buy Facebook believe those earnings will increase. However the size of this P/E ratio would, traditionally, make it not a good candidate for value investors. In the chart to the right, S&P 500 stocks are grouped by their quarterly P/E ratios from 1926 - 1990 and then the average of their ten-year return (through 2000) is calculated. Stocks with P/E ratios under 9.9 outperformed others in this study, and are generally considered "value stocks" or stocks bought "at a discount". The famous saying for value investors is "buy low, sell high" or buy when the stock is undervalued, sell when it's at par or overvalued. Where the advocate of the efficient market hypothesis would respond that the market prices in all information stocks will only be temporarily under or over valued.

Response to attacks on the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The primary evidence for the efficient market hypothesis is the preponderance of studies showing that active investors do not outperform the market. There is a substantial body of work showing that mutual fund managers do not outperform the market [3][4][5][6]. This is even true for investors that have performed well in the past. Like stocks, past performance is not an indicator of future success. And many have concluded that the fees that investment advisors charge cause their customers to underperform the market overall.

A number of studies have specifically looked at how the market responses to new information, theorizing that if it is an efficient market individual announcements should not, on average, raise the price of stocks because this information would already be priced in.[7] [8]

Fama's response to significant anomalies, where the market over or under reacts, is that "an efficient market generates categories of events that individually suggest that prices over-react to information. But in an efficient market, apparent underreaction will be about as frequent as overreaction. If anomalies split randomly between underreaction and overreaction, they are consistent with market efficiency." "The important point is that the literature does not lean cleanly toward either [over or under reaction] as the behavioral alternative to market efficiency. "

How Stocks Respond to Interest Rates

Stocks are highly sensitive to interest rates. If low-risk government bonds general significantly high levels of interest, investors will prefer them to their risky stock alternatives. As such, stock prices can go up or down based on interest rate prices (again the market should price in expectations about whether interest rates will change).

As an example, suppose that stocks are priced as the present value of the expected future stream of dividends:

\[r = \frac{D}{P} + g\]

Where \(r\) is the rate of return,

\(D\) is the dividend yield,

\(P\) is the price, and

\(g\) is the growth rate.

Suppose the "riskless rate" on government securities is 4%, and the risk premium on equity investments is 2%. Also suppose that there is a stock that is expected to have a growth rate of 2% and a dividend of $2 per share, what should the equity be priced at?

This expected rate of return, if the interest rate is 4% and the risk premium is 2%, would be 6%. And formula is as follows:

\(r = \frac{D}{P} + g\)

\(0.06 = $2.00/P + 0.02\)

\(0.04 = $2.00/P\)

\(P = $2.00/0.04 = $50.00\)

The equity should be priced at $50.

In the example on the efficient market hypothesis wiki, we said that in a market where the "riskless rate" is 4%, the risk premium is 2%, the dividend yield is $2, and the expected growth rate is 2% then the stock, priced only as the present value of the expected value of the stream of future dividends, should be worth $50.00.

This follows from the formula: \[r= \frac{D}{P} + g\]

What happens when the interest rate rises to 5%? How much should the stock price increase or decrease if nothing else changes?

Investment Strategies for Proponents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The principal suggestion from Efficient Market Hypothesis Advocates is to minimize costs (both fees and taxes if possible). Warren Buffett himself has agreed that most investors do not outperform the market, saying in his 2013 letter[9] that after his passing, his money will be invested for his family in the following way: "10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors--whether pension funds, institutions or individuals--who employ high-fee managers."

In general, large institutions (pension funds, endowments, foundations, etc.) have followed this advice and have been shifting from actively managed funds to passively managed ones. According to Morningstar's 2015 Annual report, " In 2015, actively managed mutual funds suffered more than $200 billion of net outflows, compared with net inflows of more than $400 billion for passively managed funds."[10]

Possible Paradoxes

In private, some active investors gleefully appreciate the spread of the Efficient Market Hypothesis and the shift to passively managed funds. Because the fewer people actively managing funds means fewer people to compete with. They would argue that active managers play a role in ensuring market efficiency and with fewer active managers the market will become less efficient, presenting the few that are left with more opportunities. I.E. that as more people believe in the efficient market hypothesis and passively manage their funds in indexes, the markets will become less efficient and open up opportunities for active money managers.

Overall, some consider the whole theory something of a paradox. Statistically it seems valid, but there are numerous anomalies and numerous investors with long term periods of success (for instance Berkshire Hathaway's 51 year compound annual return is 19-20% a year versus the S&P's 9.7%). There is compelling evidence on both sides, but one of the greatest advantages the theory has propelled is to point out investors' historical overreliance on investment professionals and the massive industry predicated on this need.

References

- Bachelier, L. The Theory of Speculation. Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s8275.pdf

- Malkiel, B. The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics . Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://www.princeton.edu/ceps/workingpapers/91malkiel.pdf

- Jensen, M. The Performance of Mutual Funds in the Period 1945-1964. Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://www.e-m-h.org/Jens68.pdf

- Fama, E. Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. Retrieved November 23rd, 2016, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2325486

- Fama, E. Efficient Capital Markets: II. Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/jeffrey.russell/teaching/Finecon/readings/fama.pdf

- Sommer, J. Who Routinely Trounces the Stock Market? Try 2 Out of 2,862 Funds. Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/your-money/who-routinely-trounces-the-stock-market-try-2-out-of-2862-funds.html

- Ball, R., & Brown, P. An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers. Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://www.drthomaswu.com/uicfat/1.pdf

- Fama, E., Fisher, L., Jensen, M., & Roll, R. The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information. Retrieved December 1st 2016, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2525569?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Hathaway, B. Berkshire Hathaway. Retrieved November 29th 2016, from http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2013ltr.pdf

- Morningstar, . 2015 Annual Report. Retrieved December 1st 2106, from https://corporate.morningstar.com/us/documents/PR/Morningstar-Annual-Report-2015.pdf