String Theory

String theory is a candidate for a unified theory of the four fundamental forces of nature: electromagnetism, the weak force, the strong force, and gravity. Particles in string theory are identified with particular patterns of vibration of a one-dimensional elementary object called a string. String theory is a quantum theory in that the mass spectrum of strings is discrete, so string theory is an example of a quantum theory of gravity.

Oscillations of the closed string.

Oscillations of the closed string.

One reason many physicists find string theory attractive is that it is highly constrained. It is only dependent on one dimensionless parameter, the string length \(\ell_s\). In contrast, the Standard Model of particle physics relies on nineteen dimensionless free parameters that set the particle masses and force strengths. Furthermore, the dimension of spacetime is uniquely fixed to be ten in order for the theory to be internally consistent mathematically. Lastly, in string theory one vibrational mode of closed strings must correspond to a graviton, so quantum gravity is an inescapable consequence of the theory.

String theory began as an effective theory to describe the interactions of the strong force, because the gluons that bind together quarks seemed to function a lot like rubber bands or strings holding together the quarks with some tension. Eventually, it was realized that the modes of oscillation of these strings could describe a great many more particles within a quantum framework, including the graviton, photon, and potentially the rest of the particles of the Standard Model. Although the theory is not yet complete, modern research efforts in string theory have greatly advanced the current state of understanding in major related fields of study including algebraic geometry, black hole physics, cosmology, and condensed matter physics.

Contents

Scale of Quantum Gravity

In order to understand the distance, time, and energy scales at which string theory should be a good description of nature, it is useful to describe the theory in the appropriate system of units. Researchers in high-energy physics typically use a system of units called Planck units in which \(G=c=\hbar=1\), where \(G\) is Newton's gravitational constant, \(c\) is the speed of light, and \(\hbar\) is the reduced Planck constant. These constants are fundamental to general relativity and quantum mechanics, and have units:

\[\begin{align*} [G] &= \frac{L^3}{MT^2} \\ [c] &= \frac{L}{T} \\ [\hbar ] &= \frac{ML^2}{T}, \end{align*}\]

where \(L\) refers to length, \(M\) to mass, and \(T\) to time.

Along with the Planck length, there exist similar fundamental scales such as the Planck mass and Planck time which have similar unique constructions from combinations of powers of \(G\), \(c\), and \(\hbar\).Compute the Planck length \(\ell_p\), the unique distance scale determined by combinations of powers of only \(G\), \(c\), and \(\hbar \).

Solution:

Let \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\) be the exponents of \(G\), \(c\), and \(\hbar\) respectively in the formula for the Planck length, that is:

\[\ell_p = G^{\alpha} c^{\beta} \hbar^{\gamma}. \]

The Planck length is a distance, so it must have units of length, i.e. \([\ell_p] = L\). Since the right-hand side above is equal to the Planck length, it must also have units of length. Plugging in for the units of \(G\), \(c\), and \(\hbar\) gives:

\[L = L^{3\alpha + \beta + 2\gamma} M^{-\alpha + \gamma} T^{-2\alpha - \beta - \gamma}.\]

Equating the exponents of \(L\), \(M\), and \(T\) on both sides (keeping in mind that the exponents of \(M\) and \(T\) on the left-hand side are both zero) yields the system of equations:

\[\begin{align} 3\alpha + \beta + 2\gamma &= 1\\ -\alpha + \gamma &= 0 \\ -2\alpha - \beta - \gamma &= 0, \end{align}\]

which is solved by

\[\begin{align} \begin{pmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \\ \gamma \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 3 &1&2 \\ -1&0&1 \\ -2&-1&-1 \end{pmatrix}^{-1} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} = \frac12 \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ -3 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}. \end{align}\]

The Planck length has thus been determined:

\[\ell_p = \sqrt{\frac{\hbar G}{c^3}} \approx 10^{-35} \text{ m}.\]

Which of the following is the correct formula for the Planck mass, the unique mass scale determined by combinations of powers of only \(G\), \(c\), and \(\hbar\)?

Planck units are in some sense the most natural choice of units because they are not based on any arbitrarily chosen physical system. For this reason, physicists expect that the distance, energy, and time scales involved in string theory or any other fundamental theory ought to take values close to one in Planck units. As a result, the string length \(\ell_s\) should be on approximately the same order as the Planck length.

The small value of the Planck length in S.I. units gives a clue as to why the effects of quantum gravity are not readily apparent every day. Corrections to physical models from quantum-gravitational effects become significant in physical settings that involve very short time or length scales, or very high energy scales. Examples include the very early universe and the centers of black holes.

In Bohr's simplified quantum-mechanical model of the hydrogen atom, the only allowed orbits of the electron are circular and have angular momentum \(L\) equal to positive integer multiples of \(\hbar\), that is, \(L = n \hbar\) for any \(n \in \mathbb{Z}^+\). Suppose the gravitational force were the only force binding the electron to the proton in the hydrogen atom. Find the gravitational Bohr radius (radius of the lowest energy orbit in the Bohr model) and the energy spectrum of the gravitational Bohr atom (energy \(E\) as a function of integer \(n\)).

Solution:

The gravitational force \(F_g\) binding the electron to the proton at radius \(R\) is given by:

\[F_g = G \frac{m_e m_p}{R^2},\]

where \(m_e\) and \(m_p\) are the masses of the electron and proton, respectively. The velocity of the electron as a function of radius is found by noting that this gravitational force provides the centripetal force keeping the electron in orbit:

\[F_c = \frac{m_e v^2}{R} = G \frac{m_e m_p}{R^2} = F_g.\]

Since the angular momentum \(L = m_e v R\) by definition, substituting in for the velocity yields

\[L = m_e R \sqrt{G\frac{m_p}{R}} = m_e \sqrt{GRm_p}.\]

Angular momentum is quantized in the Bohr model, which gives the radius \(R\) as a function of the number \(n\) of the orbit:

\[n \hbar = m_e \sqrt{GRm_p} \implies R(n) = \frac{n^2 \hbar^2}{G m_e^2 m_p}.\]

The lowest energy orbit is the \(n=1\) orbit, so the gravitational Bohr radius is:

\[R(1) = \frac{\hbar^2}{Gm_e^2 m_p} \approx 10^{29} \text{ m}.\]

The energy of the electron in any orbit is the sum of kinetic and potential energies:

\[E = \frac12 m_e v^2 - G \frac{m_e m_p}{R} = \frac12 m_e \left(G \frac{m_p}{R} \right) - G \frac{m_e m_p}{R} = -G\frac{m_e m_p}{2R}.\]

Plugging in for the radius as a function of the integer \(n\), one finds the energy spectrum for the gravitational Bohr atom:

\[E(n) = -G^2 \frac{m_e^3 m_p^2}{2n^2 \hbar^2} \]

The gravitational Bohr radius is larger than the radius of the observable universe, while the standard atomic length scale is about \(10^{-11} \text{ m}\). Furthermore, the energy gap between the \(n=1\) and \(n=2\) states is on the order of \(10^{-78} \textrm{ eV}\), while the energy gap between these states due to the electromagnetic force in the Bohr model is on the order of \(10 \text{ eV}\). These computations demonstrate that in atomic physics, quantum effects of electromagnetic origin vastly overwhelm the corresponding quantum-gravitational effects. Electromagnetism binds atoms far tighter than does gravity, and the energy level spacing due to gravitational effects is immeasurably small, unlike the spectral lines of electromagnetism which are easily observable in high school classrooms.

Relativistic String Dynamics and Quantization

A relativistic point particle traces out a path through spacetime called a worldline as it evolves according to its equations of motion. A relativistic string similarly traces out a worldsheet in spacetime.

The worldline of a relativistic particle, compared to the worldsheet of a relativistic string.

The worldline of a relativistic particle, compared to the worldsheet of a relativistic string.

The string worldsheet is a two-dimensional surface, typically parameterized by two variables, \(\sigma\) and \(\tau\). The variable \(\tau\) represents time, while \(\sigma\) parameterizes the string itself at a fixed instant of time, i.e. at a fixed \(\tau\), so that one endpoint of the string is at \(\sigma = 0\) and the other is at some \(\sigma = \sigma^{\ast}\). The string worldsheet in \((d+1)\) spacetime dimensions is thus described by the set of points

\[(X^0 (\tau,\sigma), X^1 (\tau,\sigma), \ldots, X^d (\tau, \sigma)).\]

where the \(X^I\) are the so-called string coordinates of the string worldsheet in \((d+1)\)-dimensional spacetime [1].

This formalism describes two unique types of strings:

Closed strings are periodic in \(\sigma\), that is, they obey \(\vec{X} (\tau, 0) = \vec{X}(\tau, \sigma^{\ast})\) for any fixed time \(\tau\).

Open strings are not periodic in the variable \(\sigma\); they are not closed loops.

From special relativity, it follows that relativistic point particles in spacetime evolve so that the length of the particle worldline is extremized. Similarly, the relativistic string evolves so that the area of the string worldsheet is extremized. Elementary differential geometry shows that one can write the following action for the string coordinates, the Nambu-Goto action, which encodes the area of the string worldsheet as a functional [1]:

\[S = -\frac{T_0}{c} \int d\tau d\sigma \sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \tau} \cdot \frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \sigma} \right)^2 - \left(\frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \tau}\right)^2 \left(\frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \sigma} \right)^2 }.\]

This action can be shown to be equal to the area of the string worldsheet up to a constant. The constant \(T_0\) in front must have units of tension and is therefore identified with the string tension. A physically equivalent action often used in advanced work in string theory is the Polyakov action.

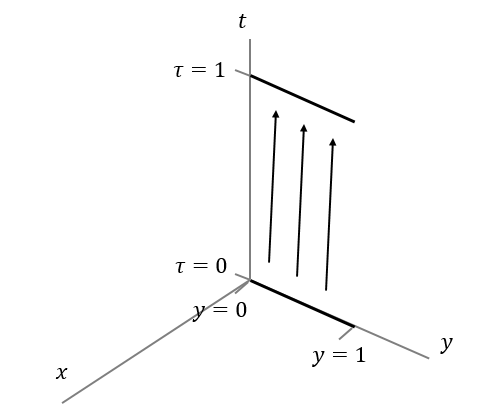

Consider a relativistic string lying on the y-axis at time \(\tau = 0\), stretching from \(y=0\) to \(y=1\). The string is parameterized so that one endpoint is at \(\sigma=0\) and the other is at \(\sigma=1\), and so that \(\tau = t\). Now allow the string to propagate from time \(\tau = 0\) to time \(\tau = 1\), leaving the string fixed on the y-axis. Find the area of the resulting string worldsheet.

If the parameterization \((\tau,\sigma)\) is chosen in a particularly simple form, the equations of motion for the string coordinates following from the Nambu-Goto action are the wave equation in each coordinate [1]:

\[\frac{\partial^2 \vec{X}}{\partial \sigma^2} - \frac{1}{c^2} \frac{\partial^2 \vec{X}}{\partial t^2} = 0.\]

Since the string coordinates obey the wave equation, it is quantitatively accurate that string motion is oscillatory.

These equations of motion must also be supplied with the boundary conditions at the string endpoints. Closed string boundary conditions are provided by the periodicity of the closed string. Open strings, in contrast, can have two types of boundary conditions [1]:

- Neumann boundary conditions:

\[\biggl. \frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \sigma} \biggr|_{\sigma = 0} = \frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \sigma} \biggr|_{\sigma = \sigma^{\ast}} = 0.\]

- Dirichlet boundary conditions

\[\biggl. \frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \tau} \biggr|_{\sigma = 0} = \frac{\partial \vec{X}}{\partial \tau} \biggr|_{\sigma = \sigma^{\ast}} = 0.\]

Neumann boundary conditions are often called "free endpoint" boundary conditions because they require that the ends of the open string are always flat and so they do not feel a force. In contrast, Dirichlet boundary conditions require that the string endpoints be fixed to some physical object. These objects are called D-branes, and can be seen as excitations related to certain states of closed strings. A D\(p\)-brane is a \(p\)-dimensional D-brane on which string endpoints are confined to move.

![Open strings with endpoints both stretching between D2-branes and lying on the same D2-brane. Image taken from [2].](https://ds055uzetaobb.cloudfront.net/brioche/uploads/iDS2gIOR2p-dbrane.png?width=1200) Open strings with endpoints both stretching between D2-branes and lying on the same D2-brane. Image taken from [2].

Open strings with endpoints both stretching between D2-branes and lying on the same D2-brane. Image taken from [2].

Rigidly rotating open strings have an unusual quadratic relation between their angular momentum \(J\) and their energies \(E\):

\[J = \alpha^{\prime} \hbar E^2.\]

The proportionality constant \(\alpha^{\prime}\) is called the slope parameter of the string and, in the original development of string theory, was a fundamental constant to describe hadrons (quarks, gluons, and the strong force). The string tension can be shown to be:

\[T_0 = \frac{1}{2\pi \alpha^{\prime} \hbar c},\]

and the string length \(\ell_s\) can also be written in terms of the slope parameter as:

\[\ell_s = \hbar c \sqrt{\alpha^{\prime}},\]

reflecting the fact that the string length \(\ell_s\) is the only free parameter of string theory [1].

Classically, since the relativistic string obeys the wave equation, its motion can be described by the center-of-mass motion of the string plus oscillations about the center of mass. When the relativistic open string is quantized, for example, the solution for the string coordinates reflects this classical form [1]:

\[X^I (\tau, \sigma) = x_0^I + 2\alpha^{\prime} p^I \tau + i\sqrt{2\alpha^{\prime}} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \left(\alpha_n^I e^{-in\tau} - \alpha_{-n}^{I} e^{in\tau} \right) \frac{\cos n\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}.\]

The first two terms on the right-hand-side describe the position \(x_0^I\) of the center-of-mass of the string and the velocity of the center-of-mass of the string via the momentum \(p^I\) in the \(I\)th direction and the time coordinate \(\tau\). The sum over oscillatory terms describes the oscillation of the string about its center of mass. In the classical description of the string, the coefficients \(\alpha_n^I\) and \(\alpha_{-n}^{I}\) essentially correspond to Fourier coefficients, as the sum corresponds to a Fourier series giving the contribution of each mode to the string oscillation. When the relativistic string is quantized, \(\alpha_n^I\) and \(\alpha_{-n}^{I}\) represent annihilation and creation operators that destroy and create excitations of each mode, in perfect analogy with the quantum harmonic oscillator.

Extra Dimensions and Compactification

String theory predicts the existence of more spacetime dimensions than the three spatial dimensions and one time dimension that we routinely observe. Bosonic string theory requires the existence of twenty-five spatial dimensions and one time dimension. This was the original version of string theory which contained only bosons in the string spectrum, and is the theory so far described by this article. Superstring theory, a more realistic but mathematically more complicated extension of bosonic string theory, demands the existence of nine spatial dimensions and one time dimension.

Since everyday experience supports the existence of only three spatial dimensions and one time dimension, string theory must explain why extra dimensions are consistent with observation. Extra dimensions do not significantly affect large-scale (everyday) physics as long as they are curled up with a sufficiently small radius, in which case they are called compact extra dimensions. To understand what a compact dimension is, one needs only to imagine an ant living on the surface of an infinitely long cylindrical tube of radius \(R\). The ant may travel along the infinitely extended dimension indefinitely. Along the other dimension, however, the ant may only travel a distance \(2\pi R\) before returning to the same coordinate in that dimension.

On short distance scales, the ant's world is two-dimensional; from far away, the ant barely moves in the compact direction before returning to the same place, so the ant's world seems one-dimensional.

On short distance scales, the ant's world is two-dimensional; from far away, the ant barely moves in the compact direction before returning to the same place, so the ant's world seems one-dimensional.

To the ant, the world seems two-dimensional in the same way the surface of the Earth seems flat and two-dimensional to humans. This is because the ant is smaller than the size \(R\) of the dimension. From far away (much further than \(R\)), however, it appears as if the ant is only traveling along the length of the tube, so the compact extra dimension is not visible on large distance scales. The analogy is not quite perfect because the ant turns upside-down as it travels in a circle around the tube; in the case of compact extra dimensions, this effect would be absent. Surprisingly, experiments are consistent with the existence of compact extra dimensions that have radii as large as \(R = 10^{-4} \text{ m}\) [1].

How does the magnitude of an electric field around a point charge scale with increasing radius in \(d\) spatial dimensions? For example, in three spatial dimensions, Coulomb's Law yields \(E(r) \propto \frac{1}{r^2}\).

Compact spaces that can describe these extra dimensions can mathematically be found by taking the quotient of a non-compact space by a discrete symmetry group.

Explain how the circle \(S^1\) is equivalent to the real line \(\mathbb{R}\) with the identification \(x \sim x + 2\pi R\).

Solution:

The given identification identifies \(0\) with \(2\pi R\). All points \(x\) between \(0\) and \(2\pi R\) are identified with points with magnitude larger than \(2\pi R\). The identification has made the real line periodic with period \(2\pi R\). One can think of this as identifying the interval \([0,2\pi R)\) with the circumference of the circle of radius \(1\).

In this case, the compact space \(S^1\) is found by taking the quotient of the non-compact space \(\mathbb{R}\) by the discrete symmetry group \(\mathbb{Z}\), the group of integers. This corresponds to the fact that points shifted by integer multiples of \(2\pi R\) are identified.

The process of forming a compact space by taking the quotient of a non-compact space by a discrete symmetry group is very important in string theory. In cases where the "identification" that defines the group action has a fixed point, this process is called orbifold compactification and the resulting space is called an orbifold of the original space. The fixed point of the group action is often called an orbifold singularity.

Explain how the complex plane \(\mathbb{C}\) with the identification \(z \sim e^{2\pi i / 3} z\) defines an orbifold compactification.

Solution:

The given identification identifies points in the complex plane with themselves rotated by \(2\pi / 3\) and by \(4\pi /3 \). The rotation of the complex plane about the origin leaves the origin fixed, so there exists an orbifold singularity at the origin. The resulting space is a cone with opening angle \(2\pi /3 \). Since the rotations of the complex plane by \(2\pi / 3\) correspond to a representation of the cyclic group \(\mathbb{Z}_3\) of order three, this space is called the \(\mathbb{C} / \mathbb{Z}_3\) orbifold.

Cross-section of a 6D Calabi-Yau manifold

Cross-section of a 6D Calabi-Yau manifold

Superstring theory predicts six extra spatial dimensions that must be compactified. A particular class of six-dimensional spaces called Calabi-Yau manifolds are excellent candidates for the shape of these six compactified spatial dimensions. Compactification on Calabi-Yau manifolds preserves important properties of superstring theory and can yield important physical predictions like the familiar three families of fundamental particles from the Standard Model and the masses of the corresponding particles. The image to the right, adapted from [3], shows a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional cross-section of one such six-dimensional space.

Gravitons and the Closed String Spectrum

The solution for the string coordinates of the closed string is similar to that of the open string, although the oscillatory terms take a slightly different form to reflect the periodicity of the closed string [1]:

\[X^I (\tau, \sigma) = x_0^I + \alpha^{\prime} p^I \tau + i \sqrt{\frac{\alpha^{\prime}}{2}} \sum_{n \neq 0} \frac{e^{-in\tau}}{n} \left(\alpha_n^I e^{in\sigma} + \tilde{\alpha}_n^I e^{-in\sigma} \right).\]

For the closed string, the operators \(\alpha_N^I\) create and destroy left-moving oscillations while the \(\tilde{\alpha}_n^I\) create and destroy right-moving oscillations. The periodicity of the closed string ultimately (though nontrivially) requires that the number \(N\) of left-moving oscillations is equal to the number \(\tilde{N}\) of right-moving oscillations. The Hamiltonian of the closed string, provided by the quantum theory, yields a formula for the mass-squared \(M^2\) of the closed string in terms of these "number operators" [1]:

\[M^2 = \frac{2}{\alpha^{\prime}} \left(N+ \tilde{N} - 2 \right).\]

Since the numbers of left-moving and right-moving oscillations are integers, the mass spectrum is discrete and thus string theory is a quantum theory. Notably, when \(N = \tilde{N} = 1\), the mass-squared of the closed string vanishes. With these values of \(N\) and \(\tilde{N}\), an arbitrary string state \(\Psi\) is a linear combination of single left-moving and single right-moving creation operators in different string coordinates \(X^I, X^J\) acting on the vacuum \(|0\rangle\):

\[\Psi \sim \sum R_{IJ} \alpha_{-1}^I \bar{\alpha}_{-1}^J |0\rangle,\]

where \(R_{IJ}\) is an arbitrary square matrix of the appropriate size. This matrix can be decomposed into a traceless-symmetric part \(S_{IJ}\), an antisymmetric part \(A_{IJ}\), and a trace part \(T\delta_{IJ}\):

\[R_{IJ} = S_{IJ} + A_{IJ} + T\delta_{IJ}.\]

Therefore, the closed string spectrum in string theory must contain massless states whose degrees of freedom are carried by a traceless, symmetric matrix. This is exactly the classical description of one-graviton states in general relativity. Thus, the closed string spectrum provides a quantum description of the classical graviton states!

How many degrees of freedom does the graviton have? That is, how many independent components are in a \((d-2) \times (d-2)\) traceless, symmetric, square matrix?

The other degrees of freedom of \(R_{IJ}\) are also important in the context of string theory. The antisymmetric part \(A_{IJ}\) corresponds to a field called the Kalb-Ramond field which gives strings a type of charge analogous to electric charge. The trace part \(T\delta_{IJ}\) is even more important, corresponding to a massless scalar field called the dilaton. The expectation value of the dilaton field sets the value of the string coupling constant and therefore governs the strength of string interactions.

Types of String Theory

The quantum excitations of the relativistic string that we have so far described are all bosons. Bosonic string theory, however, is not a realistic theory. It predicts states of negative mass called tachyons, which lead to the instability and decay of D-branes. More importantly, it does not contain fermions, which differ from bosons in that fermions are particles of half-integer spin while bosons have integer spin. The half-integer spin of fermions leads to important chemical properties, such as the Pauli exclusion principle. The presence of fermions is essential for a realistic physical theory since electrons, neutrinos, and other known fundamental particles are fermions.

Superstring theory fixes this problem by adding dynamical fermionic degrees of freedom \(\psi_1^I\) and \(\psi_2^I\) to the relativistic string, corresponding to right-moving and left-moving excitations on the open superstring respectively. If the string is parameterized so that the endpoints are at \(\sigma = 0\) and \(\sigma = \pi\), the equations of motion for the \(\psi^I\) demand that \(\psi_1^I (\tau ,0) = \psi_2^I (\tau ,0)\) and \(\psi_1^I (\tau,\pi) = \pm \psi_2^I (\tau, \pi)\). The states of the superstring fall into two sectors based on the choice of sign at the \(\sigma = \pi\) endpoint: the Ramond (R) sector for the positive sign and the Neveu-Schwarz (NS) sector for the negative sign. Excitations in the R sector versus the NS sector have different contributions to the total mass of the superstring; in fact, NS fermions have negative mass while R fermions have positive mass.

The R and NS sectors contain both bosonic and fermionic excitations of the string, since both contain the original bosonic excitations from bosonic string theory and furthermore even numbers of fermionic excitations are equivalent to bosonic excitations. However, there is a redundancy in the states described by each sector. As a result, it is standard to use the method called GSO truncation named for Gliozzi, Scherk, and Olive in which only bosonic states or fermionic states are taken from each sector. The R sector is decomposed into R+ and R- sectors describing bosonic and fermionic states respectively. Similarly, the NS sector is decomposed into NS+ and NS- sectors describing bosonic and fermionic states. However, the NS- sector contains tachyons, so the NS+ sector is always selected. As a result, for open superstrings the R- sector is used to supply the theory with fermions. Remarkably, it can be shown that the NS+ and R- sectors have exactly equal numbers of states at every mass level! This is an example of supersymmetry, a physical symmetry in which every fermionic state is paired with a superpartner bosonic state. The supersymmetry in the open and closed string spectra gives rise to the name superstring theory.

GSO truncation gives some freedom to select which sectors of the superstring spectrum will be used to describe physical states on the closed superstring. Five different types of string theory exist depending on the selection of states as well as the underlying symmetries of the theory:

Type IIA: Left-moving states can be either NS+ or R- while right-moving states can be either NS+ or R+.

Type IIB: Left-moving states can be either NS+ or R- while right-moving states can be either NS+ or R-.

\(E_8 \times E_8\) heterotic: Left-moving states are bosonic strings, while right-moving states are superstrings. The theory is invariant under the action of the symmetry group \(E_8 \times E_8\).

\(SO(32)\) heterotic: Left-moving states are bosonic strings, while right-moving states are superstrings. The theory is invariant under the action of the symmetry group \(SO(32)\).

Type I: Both open and closed strings are invariant under orientation reversal. The theory is also invariant under the action of the symmetry group \(SO(32)\).

Modern Problems in String Theory

String theory is a successful theory in that it explains the existence of gravity. However, it is a major challenge to show that string physics reduces to all of the physics of the Standard Model in the low-energy limit. That is, one must show that string theory correctly predicts the right number of particles, their masses and charges, the existence of four forces, four spacetime dimensions, and so on.

A major obstacle to obtaining concrete predictions from the string theory is the so-called string landscape problem. Since string theory predicts six extra spacetime dimensions, these six dimensions must be compactified. Orbifold compactifications of Calabi-Yau manifolds are particularly attractive candidates because compactification on Calabi-Yau manifolds leaves some supersymmetry intact, which would solve several major problems in theoretical physics. Furthermore, orbifold compactification on D-branes leads to the creation of gauge fields like the bosons of the Standard Model. However, the number of possible Calabi-Yau compactifications is enormous: estimates range from \(10^{100}\) to over \(10^{500}\). It is an open problem to find a realistic physical criterion for specifying a unique compactification.

String theory has recently provided a useful tool for the study of black hole phenomena. Computations in a string-theoretic framework were used in the late twentieth century to derive the Bekenstein-Hawking formula for the entropy of certain black holes. More well-known is the so-called AdS/CFT correspondence that relates string theory in a type of spacetime called anti-de Sitter (AdS) space to a type of quantum field theory called conformal field theory (CFT). Because the CFT lives on the boundary of the AdS space, the correspondence is an example of the proposed holographic principle in which a theory of gravity in some number of dimensions can be described by a field theory in one lower dimension. The AdS/CFT correspondence has been used to propose a resolution to the black hole information paradox in which it appears that black holes destroy information in violation of the principles of quantum mechanics.

An important route of modern research has been into the dualities present in string theory. There are two well-known dualities that relate the five types of string theories described in the previous section:

S-duality: Strings that interact with strong coupling in one theory have an equivalent description with weak coupling in a different theory. Specifically, the string coupling constant \(g\) in one theory is exchanged for a string coupling constant \(1/g\) in the dual theory.

T-duality: Spacetimes where extra dimensions are compactified in circles of radius \(R\) admit an equivalent description where extra dimensions are compactified in circles of radius \(\alpha^{\prime}/R\). Strings that wind \(w\) times around the compact extra dimensions and propagate with momentum \(p\) in the spacetime with dimensions of radius \(R\) admit an equivalent description in the dual spacetime where they wind \(p\) times and propagate with momentum \(w\). Importantly, since the string length \(\ell_s\) is on the order of the Planck length, this implies that the Planck length is the smallest physically meaningful distance scale in nature!

Relativistic quantum strings wrapping around a compact dimension have a mass dependent on the winding \(w\) and the momentum \(p\), which in turn depend on the radius of the compact dimension \(R\). The mass-squared of certain low-energy states can resultantly be written in terms of the radius as:

\[M^2 (R) = \frac{1}{R^2} + \frac{R^2}{\alpha^{\prime 2}} - \frac{2}{\alpha^{\prime}}.\]

Find the radius \(R\) at which these states are massless, i.e. \(M^2 = 0\).

Bonus: Can you figure out why this is called the self-dual radius?

There also exist dualities between the five types of string theories and a theory in eleven spacetime dimensions called M-theory. M-theory is a theory of interactions between higher-dimensional objects called branes. Specifically, M-theory is related to both \(E_8 \times E_8\) heterotic string theory and Type IIA string theory by S-duality.

It is important for string theory to admit experimental verification in order to be realistically considered a unified theory of nature. The superficially most direct route towards experimentally verifying string theory would be the discovery of the extra dimensions or extra particles predicted by string theory. The CMS experiment on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN is currently searching for extra dimensions, while the ATLAS experiment at the LHC is searching for superpartner particles. As of early 2016 neither has found evidence for either extra dimensions or particles in the energy range probed by the LHC. However, this only constrains the possible size of the extra dimensions and the mass of potential superpartner particles. Other proposed possible routes toward experimental verification include astronomical observations of black hole physics and cosmological observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation that permeates the universe, both of which may contain signature effects unique to string physics.

References

[1] Zwiebach, Barton. A First Course in String Theory. Second Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[2] Image from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/D3-braneetD2-brane.PNG under Creative Commons licensing for reuse and modification.

[3] Bryant, Jeff. Scientific Visualization and Graphics with Mathematica: Higher Dimensions from String Theory. Accessed February 13, 2015. http://members.wolfram.com/jeffb/visualization/notebooks/calabi-yau52.nb.