Integration

Integration is the process of evaluating integrals. It is one of the two central ideas of calculus and is the inverse of the other central idea of calculus, differentiation. Generally, we can speak of integration in two different contexts: the indefinite integral, which is the anti-derivative of a given function; and the definite integral, which we use to calculate the area under a curve.

Note that many integration problems will require the use of integration techniques.

Contents

Notations in Indefinite Integrals

Let and be functions related in such a way that

- The integral sign denotes integration.

- is called the indefinite integral of with respect to .

- is called the integrand.

- The differential is part of the integrand; it identifies the variable used in integration.

- is called the general anti-derivative of .

- is called the constant of integration; it is an arbitrary constant.

- If has a specific value from given conditions, is called a particular antiderivative.

Evaluating Indefinite Integrals

What is the anti-derivative of

Expanding the expression gives . Applying the reverse power rule for we have

where is the constant of integration. Note that

What is the indefinite integral of

Let , then differentiating with respect to gives , so . Thus,

where is the constant of integration.

What is the anti-derivative of

Let , then . Remember that

Back to the function ,

The integral now becomes

Integrating by parts, we let and let Then

where is the constant of integration.

Definite Integrals

Evaluate

From the previous example, we have

Setting the upper and lower limits to be and , respectively, the integral is evaluates to

Evaluate the integral

From the earlier example, the indefinite integral of is given to be

Applying the limits, we have

Integration Techniques

Main Article: Integration by Parts and Integration with Partial Fractions

Find the anti-derivative of .

We should integrate by parts.

Using the LIATE (Logarithm, Inverse trigonometric, Algebraic, Trigonometric, Exponential) rules, we have Hence,

where is the constant of integration.

Find the anti-derivative of

By partial fraction decomposition, we have

Recall that the anti-derivative of is simply , so the anti-derivative of the expression in question is

where is the constant of integration.

Problem Solving - Basic

Give your answer to 3 decimal places.

Verify by integration that the area of a circle with radius is .

By coordinate geometry, let the circle of radius have its center at the origin, then the circle satisfies the equation .

Rearranging gives . We want to integrate from to to get the area of the semicircle:

Let , then Here, to ranges from to Then, the integral becomes

The integral of can be found via the half-angle substitution. Thus, the area of the circle is

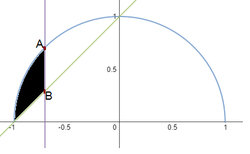

The figure at right shows a unit semicircle (in blue) and the graph of (in green).

The figure at right shows a unit semicircle (in blue) and the graph of (in green).

Let the purple line segment be the longest vertical line segment that joins the blue semicircle and green line in the domain

If is the area of the black shaded region, what is

Problem Solving - Intermediate

Evaluate the definite integral The answer must be a decimal in terms of . For example, if the calculation result is then the answer should be .